Japanese Surrender in Burma

On 12 September 1945, the official unconditional surrender of all Japanese forces in South East Asia was signed by General Itagaki in the Municipal Buildings in Singapore.

On the same day, General Ichida Jiro, Acting Chief of Staff of Japan’s Burma Area Army, formally surrendered to Brigadier E.F.E. Armstrong (Chief of Staff to Lieutenant-General Sir Montague Stopford, General Officer Commanding of the British Twelfth Army) at Government House, Rangoon.

On 24 October 1945, a formal surrender ceremony, or handing-over of swords, was held by Rangoon University’s Convocation Hall. It was watched by crowds of British troops.

A Guard of Honour was provided by 1st Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment of the 2nd British Infantry Division.

General Heitarō Kimura, Commander of Japan’s Burma Area Army, surrendered his sword to Brigadier E.F.E. Armstrong, who then presented it to General Stopford, Commander of the British Twelfth Army.

General Kimura would later be charged with war crimes, sentenced to death, and executed by hanging in Tokyo.

Successive Japanese generals then surrendered their swords to their opposite in command. Lieutenant-General Shozo Sakurai, commander of the Japanese 28th Army, surrendered his sword to Brigadier J.D. Shapland (commander of the Twelfth Army’s Royal Artillery).

The sword surrendered by Lt General Sakurai is now displayed at the Kohima Museum.

General Sakurai stayed on in a prisoner camp in Burma after the war, only willing to leave when all his men could return as well. He was repatriated to Japan a couple of years later and lived to the age of 96.

Japanese Surrender in Hong Kong

On 16 September 1945, Rear Admiral CHJ Harcourt accepted the unconditional surrender of all Japanese forces in Hong Kong.

The document was signed on behalf of the Japanese by Vice Admiral Ruitaka Fujita.

The ceremony took place at Government House, Hong Kong, with the Guard of Honour provided by men of the British Pacific Fleet.

Japanese Surrender in South East Asia

On 12 September 1945, an official unconditional surrender of all Japanese forces in South East Asia was signed by General Itagaki in the Municipal Buildings in Singapore.

Under grey skies threatening rain, cars arrived at 10.20 carrying General Sir William Slim, commanding Allied Land Forces, Admiral Sir Arthur Power, C in C East Indies, & Air Marshal Sir Keith Park, commanding Allied Air Forces. They were watched by crowds of excited spectators, cramming the enclosures, hanging from trees & standing on rooves of nearby buildings. Within minutes, cheering & clapping heralded the arrival of the Supreme Commander, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, in an open car with his Deputy, Lt. General Raymond Wheeler, US Army.

Guards of honour presented arms & the Royal Marines’ band struck up ‘Rule Britannia’. This was followed by a flypast.

Then the mood changed, as the Japanese contingent arrived amidst catcalls, boos & whistling. They filed into the Council Chamber, led by Maj General Itakagi.

Admiral Mountbatten entered last & motioned the assembly to sit. He then read a telegram from Field Marshal Terauchi, appointing Maj General Itagaki to represent him, as he himself was too ill to attend. Mountbatten agreed to this, but insisted that Terauchi surrender in person as soon as he was well enough. (This happened in Saigon on 20 November 1945.) Mountbatten then announced

“I wish to make it entirely clear that the surrender today is no negotiated surrender. The Japanese are surrendering to our superior forces.” (26)

The Instrument of Surrender was read out by a staff officer & then passed to Itagaki for his signature. After Terauchi’s official seal had been pressed heavily on the document, it was passed to Mountbatten for his signature. This was repeated ten more times, each copy being passed in turn from Itagaki to Mountbatten.

The Japanese then left.

After a suitable interval, Admiral Mountbatten moved outside to read his Order of the Day. It began

“I have just received the Surrender of the Supreme Commander of the Japanese forces who have been fighting the Allies and I have accepted the Surrender on your behalf. I wish you all to know the deep pride I feel in every man & woman in the Command today. The defeat of the Japanese is the first in history. They are finding it hard to accept the defeat or to wriggle out of the Terms of Surrender.” (26)

When he had finished, Admiral Mountbatten called for three cheers for His Majesty the King & then walked to a flagpole for the formal hoisting of the Union Jack. The flag used was the one carried when Singapore fell in 1942. It had been hidden in Changi Gaol throughout the occupation. National Anthems of the Allies were played.

Finally, buglers sounded the “attention” & the guards of honour presented arms as Admiral Mountbatten drove away.

A short film showing highlights of the occasion can be watched here.

Victory Parade in Rangoon

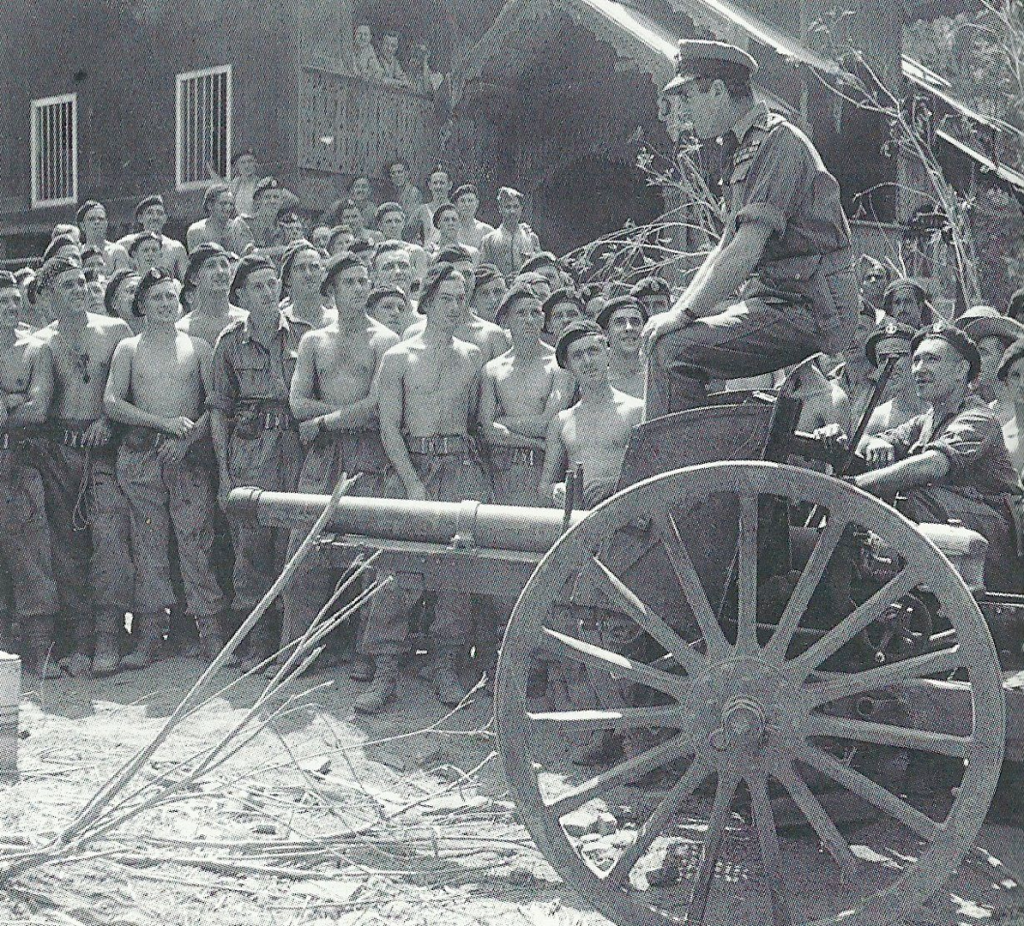

On 15th June 1945, a victory parade was held in Rangoon to celebrate the defeat of the Japanese armies in Burma.

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia, read an address to the assembled troops from His Majesty The King George VI.

The address was followed by a march past.

The Kohima Museum in 2024

Three staff, all unpaid volunteers, have worked at the Kohima Museum in 2024: Bob Cook (curator since 2008), Brian Ward (since 2012) & Bob White (since 2023). The team is pictured below in a C47 transport plane, which can be visited at the excellent Yorkshire Air Museum at Elvington, just outside York. Visitors can go inside the cargo hold & look into the pilot’s cabin.

The team were kindly invited to a Military Memorabilia event at the outstanding York Army Museum. We had the opportunity to tell many of the visitors about the Museum. It was disappointing to discover that most of those we spoke to had never heard of the Battle of Kohima, despite their evident interest in military history. There is clearly much work to be done to raise awareness of Kohima & the Burma Campaign. In contrast, we met a D-Day veteran who commented that the guys in Burma had it tougher than the heros of the Normandy Landings!

As a recent recruit, Bob White was sent on a five-day course for new curators at the National Army Museum in London. This included a visit to the Household Cavalry Museum.

Brian Ward has been an invaluable member of the team for 12 years, responsible for the immaculate presentation of the Museum. On his 80th birthday, Brian stepped back from this busy role. He was heard to mutter “One Bob’s bad enough”. His colleagues & the Museum’s Trustees are extremely grateful for all his tremendous work & hope that he will be a regular visitor.

A major effort has been made in 2024 to increase the Museum’s activity online. The website is our most effective medium for widening awareness, but it had stagnated in recent years.

To this end, the old pages were refreshed in 2024, with new images & content, & a range of new pages were built to broaden coverage. Pages have been added that describe the battles of Admin Box, Imphal, Jessami & Kharasom, as well as Air Power, Armour & the Naga. An Object of the Month page was introduced to describe some of the treasures of the Kohima Museum. A page about the Battle of Sangshak is being prepared for the New Year.

A Blog was introduced in March to coincide with the 80th Anniversary of the Battle of Kohima. New posts were added to this blog each day to describe events at Kohima on the corresponding date in 1944, from the crossing of the Chindwin by 31 Division to its miserable retreat along the ‘Road of Bones’. This material can now be read in its entirety at The Battle of Kohima – Day By Day. Daily coverage through the spring & summer was very demanding. The blog has since settled into a much more manageable routine of one new post each week, with ad hoc material about the Burma Campaign.

The effort has been rewarded by a substantial increase in traffic, with daily visits to the website increasing from 32 per day in February to 66 per day in November. Overall, the website has been visited more than 13,000 times since January 2024, taking the story of the Burma Campaign to a huge audience.

Activity has also increased on Kohima Museum’s Facebook page, which has 3,600 followers. A photo of curator Bob Cook at the Museum one Saturday morning received 374 likes, our new Facebook record. There’s no accounting for taste!

With the aim of reaching more youngsters, Kohima Museum opened an Instagram account. This is slowly building a following, but numbers are low so far (114 on December 31). Please follow us if you use Instagram.

It is hoped that social media activity will increase footfall to the Museum. Indeed, vistor numbers rose in 2024. This increase was also assisted by a banner to advertise the our existance to passers by & local traffic. It was the first time such an advertisement has appeared on the railings of Imphal Barracks. We are grateful to the Garrison Commander for permission to do this.

As ever, the annual Kohima Remembrance Service was followed by the Museum’s busiest afternoon of the year, with over a hundred visitors.

We were delighted to welcome many relatives of Kohima veterans. For example, Mr Richard Winstanley, son of Major John Winstanley, who commanded B Company of the Royal West Kents at Kohima.

Another example was Mrs Akiko Macdonald, whose father fought at Kohima with the Japanese 31st Infantry Division.

We were visited by three generations of family of Kohima veteran Dennis (Joe) Dernie, Royal Army Service Corps, 2nd Division.

It was also splendid to see Mrs Celia Grover, daughter-in-law of Major General Grover, who commanded the Allies at Kohima.

We were visited by a serving general, Major General Sajith Liyanage of the Sri Lanka Army.

It was great to receive visitors from all over the world, including New Zealand, China, Japan, Singapore, India, USA, Greece, Ukraine, Norway & Germany, not including any who forgot to sign the visitors book.

To keep alive the memory of the Burma Campaign, it will be essential to engage members of the younger generation. To this end, we have been very glad to host visits from students at the local universities.

It was also a pleasure to work with two history students from York St John University, who carried out a project about the Nagas at Kohima.

The curators of Kohima Museum have kept busy during 2024. It is hoped that the increase in visits online & in person will continue, to keep alive the memory of the Burma Campaign.

25 November 1944: Unveiling of the Memorial at Kohima to 1st Battalion Royal Scots

The Royal Scots Memorial was constructed from local stone by the Pioneer Platoon. It is sited at Kennedy Hill, on the Aradura Spur, & was unveiled on 25 November 1944 by the Battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Masterton Smith, who had fought throughout the Battle of Kohima.

There are 74 names on the Roll of Honour.

Creation of the 2nd Division Memorial

The British 2nd Infantry Division Memorial was designed by Lieutenant Jamie Ferrie, 506 Field Company, Royal Engineers, who was a professional architect before & after the war. His sketches were developed using a wooden model. Construction began on September 19, two months before the unveiling. The cost was met by subscription within the Division.

Near Maram, at Milestone 80, were a number of obelisk stones, erected by Nagas in days gone by. Permission was given for one of these to be dug out by 506 Field Company to provide the main headstone of the memorial. It was about 16 feet high, 3 feet wide, 18 inches thick & estimated to weigh 17 tons.

The obelisks lay about one mile from the main road at the end of a very steep slope. A bulldozer cut a zig-zag track, which allowed access by a huge Scammel lorry with a 45-ton winch & a 3-ton crane. Sappers dug earth anchors behind the monolith & reeved blocks & tackle to hold the weight of the upended stone. Then it was gradually lowered to the ground.

Once horizontal, the monolith was harnessed & then drawn by the Scammel onto teak rollers, which were passed from the rear to the front of the stone as it rolled downhill over them, restrained by the winch.

On reaching the Imphal Road, the Scammel lifted the stone onto a tank-transporter, where it was secured by ropes. At one point on its journey to Kohima, the rear wheels of the transporter slid off the road at a sharp bend. The ropes broke & the monolith slid off into a culvert. There it remained overnight, whilst the Scammel was summoned. This lifted the transporter back onto the road & then replaced the stone, allowing its journey to continue.

At Kohima, the monolith was lifted off the transporter near the foot of Garrison Hill & then manhandled by two hundred Nagas into its chosen position. They refused to accept payment for this demanding task.

The monolith carries the Kohima Epitaph:

When you go home

Tell them of us and say,

For your tomorrow

We gave our today

These words were based, with minor amendments, on a translation by classicist John Maxwell Edmunds of a Greek epitaph written by Simonides of Ceos for the 300 Spartans under Leonidas who stood at Thermopylae against the vast Persian army of King Xerxes in 480 BC.

Below the epitaph is a plaque of dedication. Another plaque, on the reverse of the plinth, describes the battle. Behind the monolith runs a semi-circular wall of grey dressed stone into which were set a series of thirteen bronze panels engraved with the Roll of Honour of those killed in the battle.

The Memorial was unveiled on 18 November 1944 by Lieutenant General Sir William Slim, Commander of 14th Army, in the presence of representatives of all the Division’s regiments. The ceremony included hymns, a lament played by kilted pipers, & The Last Post played by a bugler.

Chisels were made in Divisional Workshops for the engraving, which took several months to complete. Accordingly, the engraved panels were absent when the memorial was unveiled.

When the panel with the Kohima Epitaph was added, the wording was slightly different from what had been intended, with ‘THEIR TOMORROW’ instead of ‘YOUR TOMORROW’.

It was not until 1963 that the wording was corrected to what had been intended, by erection of a new panel.

In 1974, it was noticed that three of the bronze panels bearing the Roll of Honour had been stolen from behind the monolith. The remaining ten were shipped to the U.K. for their preservation. They were replaced by engraved stone tablets.

Nine of the surviving bronze panels were received by the regiments they honoured. The tenth is displayed at the Kohima Museum in York.

My grandfather came back

The Battles of Imphal & Kohima were honoured at the Festival of Remembrance in the Royal Albert Hall, London, on November 10 2024.

The cameras focused on a lone figure standing in the arena.

“My name is Lauren Turner-Roden & my grandfather, Raymond Street, fought with the Royal West Kents at Kohima.

Too young to understand his stories while he lived, I will be forever grateful that he left our family his written memories. He said at Kohima

‘I was twenty-four but felt a hundred. All of us young men had seen too much in too short a time. I believe they called it living their lifetime in a day. I don’t know about that, but what we had seen during the last few months was enough for anyone. Our casualties were mounting. We lost several men that day. Not one was older than twenty-one. Would it be our turn next? Every man on this hill had been picked by fate & some, maybe all, would die.’

My grandfather came back, allowing me to stand here today to share his memories with you.

The Kohima epitaph is engraved on the memorial to the 2nd British Division in the cemetery at Kohima. It makes a simple request: When you go home, tell them of us & say, for your tomorrow we gave our today.”

My Dad Cried on Remembrance Sunday

By Robert Street

Written in memory of his father Private Raymond Street, 4 Battalion, Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment.

He didn’t take long to prepare

A cup of tea, the TV, sat in his favourite chair

At 11, he stood to attention, straight and erect

It was his way of showing them respect

My Dad cried on Remembrance Sunday

Were they tears of joy; no

Tears of regret; maybe so

Tears of gratitude for he made it home

Tears of sorrow for those left buried alone.

My Dad cried on Remembrance Sunday

It doesn’t take long to prepare

A cup of tea, the TV, sat in my favourite chair

At 11, I stand to attention, straight and erect

It’s my way of showing him respect

It’s my turn to cry on Remembrance Sunday

Are they tears of joy; no

Tears of regret; maybe so

Tears of gratitude for he made it home

Tears of sorrow for I now watch alone

It’s my turn to cry on Remembrance Sunday

From “Soldier Poets of the 2nd British Infantry Division” by Bob Cook & Robin McDermott.

The flag was captured by the Japanese when they took Singapore in 1942. Behind the flag is Countess Mountbatten. To her right is Raymond Street of the Royal West Kents.

Kohima revisited in July 1944

Captain W. Machlachan had served with the Burma Regiment as part of the garrison throughout the siege of Kohima, until relieved on April 20. Three months later, he returned to the scene of his ordeal. Below is an abridged version of his description of Kohima in July 1944.

“Though much has been done in the last month to restore a peaceful atmosphere to Kohima, we are forcibly reminded at every turn of the War, although nature is doing her best to efface the gashes that man had made on the earth.

The end of the battle coincided with the monsoon. The lush undergrowth which appeared with the rain has grown over trenches & shell craters. Rain has washed away the earth from the roofs & walls of hastily dug fox-holes, causing them to collapse into shapeless pits with roof timbers jutting out where they subsided. Because of this, it was only with difficulty that my orderly & I have discovered the bunker in which we had spent nearly three weeks in April & with which we were so familiar that we thought we would remember it in every detail for years to come.

Though nature is doing its best to remove traces of the battle on the ground, it will take many years before the trees which grew thickly on the hill on which the Garrison stood firm can be replaced. They point skywards in bleak & charred nakedness &, with hardly one exception, are completely denuded of leaves, silent witnesses to man’s outrages.

Already many of the shattered buildings have been bull-dozed away. This includes the Deputy-Commissioner’s Bungalow at the foot of Garrison Hill, around which there was much fighting during the first week until the garrison withdrew up the Hill. On its site a cemetry is being made for troops who fell in the original defence & the subsequent relief.

The Hill is still strewn with the aftermath of battle, such things as it had not been worth anyone’s while to pick up. The barbed wire that we had so hastily strung in front of our trenches is hanging tangled with signal cable that had fallen from trees. Parachutes which had brought us medical supplies, water & ammunition from the air, flap in shreds from tree branches where they had been snagged during dropping. Blackened petrol drums are still at the foot of a cleft where they had been flung & set on fire to prevent their falling into the hands of the Japanese.

Here & there are still enemy corpses, recognisable as such now only by the rags of uniform which hold bundles of bone together. One was warned to leave such bundles severely alone in case they covered booby traps.

I find it odd to walk freely about the site of our defences unhampered by the attentions of Japanese snipers. We find it even odder to drive about the roads & tracks which had been in areas occupied by the Japanese.

Driving round the Naga Village itself, not a single undamaged building can be seen. The majority of the huts have at least one of their plaster walls torn away & not one corrugated roof has escaped the riddling shrapnel & bullet fire.

To leave a picture of post-invasion Kohima as the shambles of a battlefield would, however, be false. Already new buildings are replacing those destroyed & the holes in the roofs of sound buildings are being stopped with pitch.” (11)

These hands

Gunner Richard George of 99 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, had a distressing experience whilst supporting the vanguard of 2 Division’s advance. One of the Royal Scots’ casualties had been put in a shallow grave, but the monsoon had washed away some of the soil placed over him & exposed his hands. Gunner George recorded how he had covered them up:

“Some of their bodies had been hastily buried and it was over one of these graves I stumbled when we moved in later. The village was still burning, and I knelt and covered the exposed hands of the dead Scotsman in his shallow grave.”

Moved by the experience, he wrote a poem that same night, which he called “These Hands” (16)

Beside the burnt-out remnants of this place

I saw the lifeless hands above the earth

Here then was war the horror of its face

For this, for this, a man was given birth

The shallow grave would scarce the body hide

Akimbo sprawled the hands were still and grey

I could not pass but knelt down by his side

To scrape the soil and cover from the day

These hands, I said, once moved and felt and knew

The warmth of other hands, and touched things dear,

Perhaps had picked firm fruit or flowers grew

Or turned bright wheels or trailed through water clear

But now no life beneath my burning touch

I tried to hide which might have been my own

Dead fingers here which once at life did clutch

But now I press them down, alone – alone

It seems so strange, the unexpected things

Which one is called to do in times like these

My mind revolves and childhood memory brings

The tears I shed, and know I cannot grieve, Only some deep-down pain I cannot show

Wells in my heart and floods without a sound

For this quiet heap where grasses soon will grow

For him who knows me not beneath this mound.

Yosegaki Hinomaru flags

Many Japanese soldiers carried their own flag for good luck. The flags are known as “Hinomaru”, which translates as “circle of the sun”. Flags presented early in the war were made of silk, but cotton became more common as resources became scarce. They would be bought in a shop & then personalised with the name of the recipient, friends & family, as well as messages of hope, good luck & patriotic slogans.

The flags were popular souvenirs for Allied soldiers, in most cases taken from dead Japanese.

The flag above was found in 1944 by men of 1/1 Punjab Regiment. Its messages include “divine fighting spirit”, “defeat the US and UK”, “leadership spirit will reach thousands of miles”, “huge accomplishments in distant lands”, “for construction of world history”, & “beautiful death with honour and loyalty”.

A feature by the National Army Museum is the source of the above images & provides more examples & information about Yosegaki Hinomaru flags.

Beasts of Burden

Japanese 31st Division had to cross mountainous jungle terrain to reach Kohima, 120 miles away. There were a few narrow, winding tracks, but no roads that could take motor transport from the frontier. An average infantryman carried about 100 lbs, so heavy that he needed help to stand up; this included his personal supply of rice for 20 days. Mules could carry 160 lb & were used in huge numbers, as were horses.

Mutaguchi attempted to use bullocks to transport stores & munitions, providing his army with a source of fresh meat when needed, but these beasts plodded far too slowly. They were used to pulling carts or ploughs, not to carrying burdens on their backs, & they would stop frequently & stubbornly refuse to move. This was hugely frustrating for troops rushing to reach their objective. Captain Shosaku Kameyama expressed the opinion that

“These ideas of our top brass proved to be wishful thinking, which disregarded the harsh reality.” (5)

Captain Kameyama recorded that 700 oxen were allocated to his battalion & one of its four rifle companies was converted into a transportation unit responsible for them. This was less than popular for these young fighters, eager to prove themselves in battle.

17,000 of the beasts of burden supporting the Japanese, mules, pack ponies & bullocks, perished in the Invasion of India.

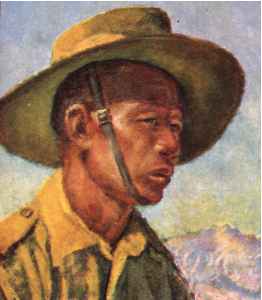

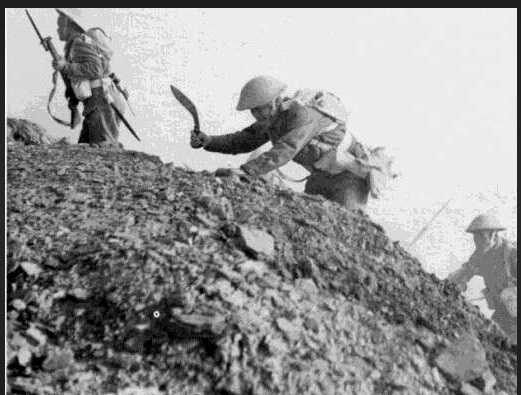

Gurkha

Gurkhas are mercenaries from Nepal, renowned for their courage & fortitude. They have fought with the British since 1815, formerly as part of the Indian Army. A British officer of a Gurkha regiment recorded:

“Gurkhas were wonderful chaps to command. They had a lovely sense of humour. You had to prove yourself, but once they liked you they would do anything for you.” (4)

After Indian independance, Gurkhas transferred from the Indian Army to the British army, where the Gurkha Brigade continues to serve with distinction.

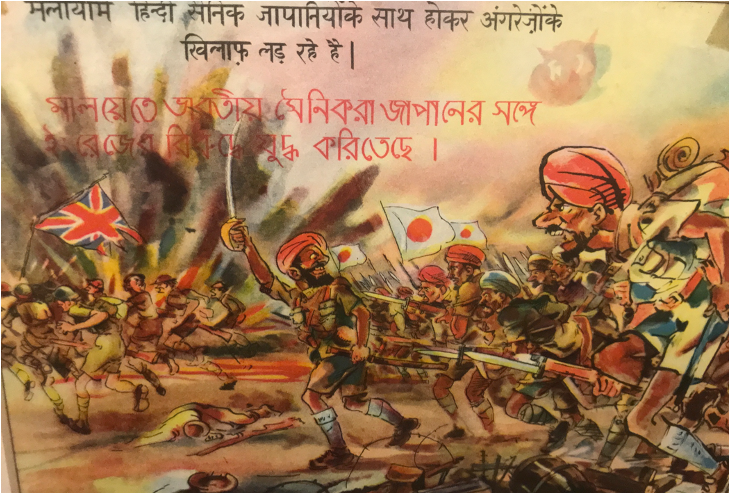

Indian National Army (INA)

Subhas Chandra Bose had been a leader of the radical, wing of the Indian National Congress, becoming Congress President in 1938. He was replaced in 1939 following differences with other leaders and later placed under house arrest by the British, for promoting civil unrest.

Bose escaped from India in 1941 and traveled to Berlin to appeal to Hitler for support in securing independence for India by force. A brigade was established, termed the Free India Legion, of 4,500 Indians captured by the Germans in North Africa.

Bose then turned to the Japanese and, with their assistance, organised the Indian National Army. A 16,000 strong Division was assembled, composed largely of Indian soldiers of the British Indian Army who had been captured by the Japanese when Malaya & Singapore were conquered. There were executions of some Indian prisoners of war who refused to join the INA.

The INA Division supported the Japanese 15th Army when it invaded India in March 1944, urged on by Bose with the slogan “Onward to Delhi”.

An anonymous Indian corporal explained:

“I joined the INA after hearing Netaji. The Japanese were not cruel to anyone. They said the Asians should fight for their independence, and all Asians should be independent. We were fully confident that the Japanese would hand independence to India, as they had done to the Burmese, the Malays, the Thais; all the Asians. The Japanese remained in Burma because Nehru said on the radio that he didn’t need any help from outside”. (2)

There was no mention of the 14 million, mostly civilians, who died during the Japanese occupation of China. Netaji means “Respected Leader” in Bengali, a title applied to Subhas Chandra Bose.

Two Million Indian Volunteers

Despite the civil unrest, more than 2 million Indians volunteered to join the Indian Army & fight alongside the British. It was the largest conscript army in history. Sometimes referred to as the British Indian Army, to avoid confusion with the Indian National Army (INA).

Although junior officers were often Indian, the senior offices were British. Many Indian Infantry Brigades contained one British and two Indian battalions. For example, the 161st Indian Brigade, which stopped the Japanese from taking Kohima, comprised the 4th Battalion Royal West Kents, the 1st Battalion 1st Punjab and the 4th Battalion 7th Rajputs.

By 1945, 14th Army troops were 87% Indian, 10% British & 3% African. A report produced by the British War Office, based on interrogation of prisoners, was disappointed to record that the Japanese considered that Indians & Gurkhas were better soldiers than the British.

Queen of the Nagas

The photograph & caption below is from the Bombay Chronicle, 9 September 1945, and shows the marriage of Ursula Graham-Bower, who lived with the Naga people. She led a group of Naga tribesmen to provide valuable intelligence about the strength and activities of the Japanese. Her husband was a British intelligence officer of V-force.

In her own words:

“My parents could not afford to send me to Oxford, so instead I went to live among the Naga tribes and carried out ethnographic work. When war broke out I … helped start a Watch and Ward scheme in Nagaland. My job was to collect information on the Japanese and send it back by runner. But it had problems. There was no hope I could conceal myself in the Naga village. I am too tall and light skinned. In Burma when British officers were occasionally hidden, the Japs tortured the villagers until the officer gave himself up. I fixed up with Namkia, the headman, that I wasn’t going to be taken alive. So I would shoot myself, and he would take my head in, if the pressure on the villagers became unendurable”. (2)

Forgotten Army

The 14th Army was formed in late 1943 to fight the Japanese. Thirteen infantry divisions served within it, of which eight were Indian, three African and two British.

The British referred to themselves as the Forgotten Army, because press coverage back home always focused much more on events in Europe.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Commander South East Asia, used to get a laugh from the troops by joking:

“I know you think of yourselves as the forgotten army, well let me tell you you are not forgotten…”

…pause for effect…

“…nobody even knows you’re here!” (1)